Transforming Public Understanding of Grenada’s African Religious Heritage

Orisa worship and the Spiritual Baptist faith are two African-inspired religions which were subjected to repressive colonial legislation in Grenada. Although no longer enforced, the laws remain, and both groups are largely unrecognised by government, stifling their civic, political, and cultural participation. Public awareness of their histories and traditions is minimal. Working with the cultural collective the Shrine of the Seven Wonders of Africa, this project aims to raise that awareness to inform education curricula, promote legislative reform, and change government policy, thereby promoting and safeguarding African religions in Grenada.

This project draws on oral and archival research conducted by Dr. Shantel George, a historian specializing in transatlantic slavery at the University of Glasgow. Her book, "The Yoruba Are on a Rock": Recaptured Africans and the Orisas of Grenada, is set to be published by Cambridge University Press in 2025.”

This project is funded by the University of Glasgow’s AHRC Impact Acceleration Account Fund.

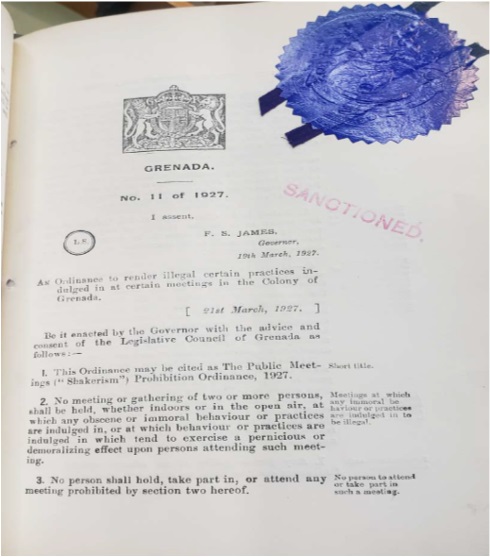

Banning the Spiritual Baptist Faith: The Shakerism Prohibition Ordinance, 1927

The Spiritual Baptist Faith is an African-inspired religion originating in nearby St. Vincent among formerly enslaved Africans, which transformed the religious landscape of Grenada and Trinidad from the early twentieth century. Its key practices include baptism, thanksgiving (especially feasts), mourning (spiritual travel)*, pilgrimages, candle lighting, drumming, and ‘doption’ (the expounding of various tones and sounds). Sunday services begin with the ringing of a bell, followed by the lighting of candles. Water, rice, oils, flour, and peas are then placed at the four corners of the altar. Altars are commonly decorated with an assortment of flowers, glasses of water, calabashes, goblets (clay water pitches), vases, and sometimes also Bibles and crucifixes.

*A period of prayer, fasting, and renunciation in which the mourner spends most of the time lying on the floor of a dark room, sometimes in a coffin. During mourning, the initiate travels spiritually to different lands, receives instruction through visions and dreams, and acquires spiritual gifts and their role within the church.

Mother Annie’s Spiritual Baptist Church, La Potrie, St. Andrew

In mid-nineteenth century St. Vincent, the emergence of these practices troubled Wesleyan Methodists. One Methodist report dismissed these beliefs as no more than an ‘insane attempt, to blend and unite the excitements, stimulants, delusions, and superstitions of Africa, with the profession of Christianity.’ Officials and non-members called these practices ‘Shakerism,’ alluding to how the bodies of adherents shook as they went into trances, reminiscent of the mid-18th century Shaker church in England. Colonial officials and missionaries described members held ‘open air orgies’ with frenzied sounds, grunting, leaping, clapping, and rolling on the floor. Consequently, members were expelled from the Wesleyan Church, and in 1862, the military destroyed a ‘Shaker’ chapel after discovering some members participated in labour riots. In the late 1940s, to distance themselves from the negative associations with Shakerism during their fight for religious freedom in St. Vincent, followers renamed themselves Spiritual Baptists.

A public inquiry determined that the Shakers were not a religious group and should be prosecuted as a public nuisance. In 1912, the St. Vincent Shakerism Prohibition Ordinance was passed, and many members were imprisoned, fined, and subjected to hard labour. Persecution forced adherents to flee, spreading their faith throughout the Eastern Caribbean. Spiritual Baptists made a significant early impact in Trinidad, but faced similar challenges there; in 1917, Trinidad enacted a comparable Prohibition Ordinance. Fleeing Spiritual Baptists also reached Grenada, situated between St. Vincent and Trinidad. As in St. Vincent, concerns were raised about the faith in Grenada, and on 14 March 1927, ‘The Public Meetings (“Shakerism”) Prohibition Ordinance’ was passed in Grenada.

Like the legislation in St. Vincent and Trinidad, the act prohibited gatherings of ‘two or more persons’ where ‘obscene or immoral behaviour or practices’ occurred, and activities which had a ‘pernicious or demoralizing effect.’ If such a meeting was suspected, the police were authorized to enter the premises and record the names and addresses of those present. Those found guilty could be fined £50 or face imprisonment, with or without hard labour, for up to five months. The act stifled the practice of African-related observances, affecting both Spiritual Baptist and Orisa practitioners. Applied widely by the colonial state, the 1927 legislation empowered legal authorities to monitor, restrict, and suppress meetings and gatherings deemed as a threat to the colonial order. Further, in conjunction with obeah-related acts put in place during and after enslavement, elements integral to the practice of Orisa—such as night drumming, healing, divination, animal sacrifice, and occult books and materials—were prohibited.

Although the act has since been modified and no longer refers to ‘Shakerism,’ the wording of the current act remains almost identical to that of 1927. There have been efforts towards recognition: in 1975, a large Spiritual Baptist Church in Grenada was incorporated into the Grenada United Spiritual Baptist Church Incorporation Act of 1975, which permits the trustees of that church to acquire property and land. Today, adherents continue to seek recognition and legitimacy in Grenada.

Sources

Interviews

Bishop John Noel, interview with Shantel George, Hanwell, London, 7 October 2013.

Primary Sources

- George’s Chronicle and Gazette, 18 October 1912.

- SOAS, MMS FBN West Indies Correspondence 4, Babou Circuit Report 1851, St. Vincent, Synod Minutes.

- TNA CO 103/26, Public Meeting (“Shakerism”) Ordinance, no. 11 of 1927.

Secondary Sources

- Boa, Sheena. ‘Colour, Class and Gender in Post-Emancipation St. Vincent, 1834-1884.’ PhD diss., University of Warwick, 1998.

- Cox, Edward. ‘Religious Intolerance and Persecution: The Case of the Shakers in St. Vincent, 1900–1934.’ Paper presented at the 18th Annual Conference of the Caribbean Studies Association, 24–29 May 1993.

- Fraser, Adrian. From Shakers to Spiritual Baptists: The Struggle for Survival of the Shakers of St. Vincent and the Grenadines. St. Vincent: Kings-SVG Publishers, 2011.

- Glazier, Stephen D. Marchin’ the Pilgrims Home: Leadership and Decision-Making in an Afro-Caribbean Faith. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1983.

- Grey-Burke, Archbishop. A Brief History of the Shouter Baptist Faith in Trinidad & Tobago. Maraval, Trinidad: Council of Elders Spiritual Baptist Shouter Faith of Trinidad & Tobago, 2002.

- Henry, Frances. Reclaiming African Religions in Trinidad: The Social-Political Legitimation of the Orisha and Spiritual Baptist Faiths. Barbados: University of the West Indies, 2003.

- Houk, James. Spirits, Blood, and Drums: The Orisha Religion in Trinidad. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1995.

- Lum, Kenneth A. Praising His Name in the Dance: Spirit Possession in the Spiritual Baptist Faith and Orisha Work in Trinidad, West Indies. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers, 2000.

- Paterson, J. comp. Grenada. Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1901. St. George, Grenada: Government Printing Office, 1902. Accessed 24 May 2016. https://archive.org/details/cu31924032177101/.

- Smith, M. G. Dark Puritan: The Life and Work of Norman Paul. Kingston, Jamaica: Dept. of Extra-Mural Studies, University of the West Indies, 1963.

- Zane, Wallace W. Journeys to the Spiritual Lands: The Natural History of a West Indian Religion. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Online resources

- Laws of Grenada (last accessed 10 March 2023).

- ‘Public Meetings Prohibition and Control Act,’ Laws of Grenada (last accessed 10 March 2023).

- ‘Spiritual Shouter Baptist Liberation Day.’ National Library and Information System Authority (accessed 2 May 2014).